Even for a brand known for doing things in a big way, Nike had an outsized presence at this Olympics, spending more in Paris than it has at any previous Games. In addition to outfitting more than 100 federations across team and individual sports (including Team USA) with kits that featured a reinvented Nike Air, the sportswear brand also:

- Hosted an exhibition at the Centre Pompidou art museum inspired by its Air Max 1 shoe;

- Posted six AR-enabled statues of Nike athletes measuring eight- to 11-meters high outside the Palais Brongniart, former home of the Paris Stock Exchange;

- Debuted a new sneaker created specifically for breakdancing, which made its Olympics debut at these games; and

- Created an elite Athlete House for Nike athletes that featured recovery services, places to relax and “a self-expression space” for hair, makeup and even “tooth gems.”

“The Paris Olympics offers us a pinnacle moment to communicate our vision of sport to the world,” said CEO John Donahoe in June on the company’s Q4 earnings call with investors. “This is led by breakthrough innovation and announced by a brand campaign that you won’t be able to miss.”

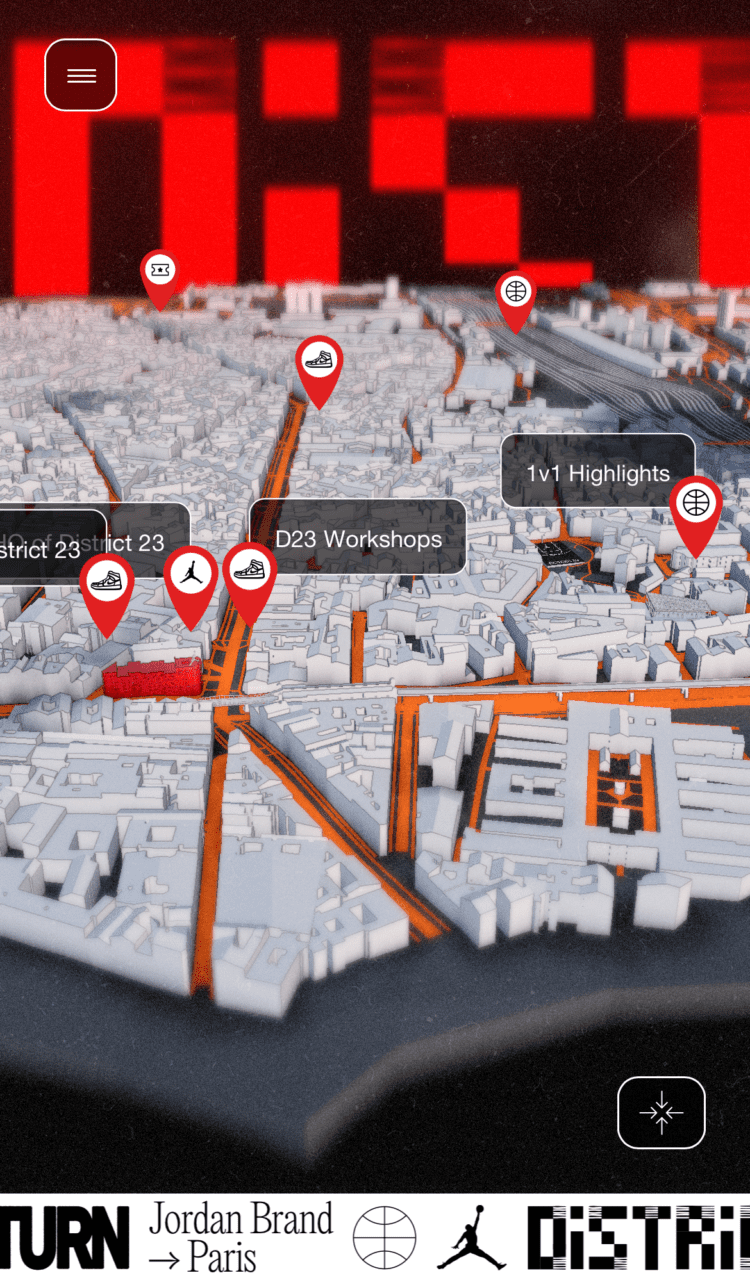

That was certainly true, but perhaps the most interesting Parisian outing for the embattled brand was one of its least splashy: A bit removed from the heart of Olympics activity at the city’s center, Nike’s Jordan Brand hosted a six-week installation called District 23 in Paris’ 18th arrondissement. The collaboration featured a compelling combination of brand and purpose that, while more soft-spoken, may end up being more impactful.

Reinventing an Iconic Parisian Department Store

This neighborhood was chosen purposefully, having long been home to immigrant communities across many backgrounds. The goal, according to Nike, was to “elevate the neighborhood into a global sport and cultural hub.” In addition to a café, art exhibition, retail space and educational hub located in the now defunct but still iconic Tati Barbès department store, the installation also included the maintenance of several basketball courts and outdoor spaces in the neighborhood where one-on-one basketball tournaments, open play and shootarounds were hosted throughout the summer.

Advertisement

“District 23 is Jordan’s love letter to the diasporic cultures and international youth who inform basketball and all its dimensions — a living, breathing example of how to use sport’s greatest stage as an accelerator for lasting impact that serves the entire community, particularly the next generation,” said the company in a statement.

Founded by Jules Ouaki in 1948, the Tati department chain transformed the fashion industry with its low-cost textiles and distinct gingham branding. The company’s first store debuted in Paris at the Barbès location along with its slogan: “Tati, les plus bas prix (Tati, the lowest prices).”

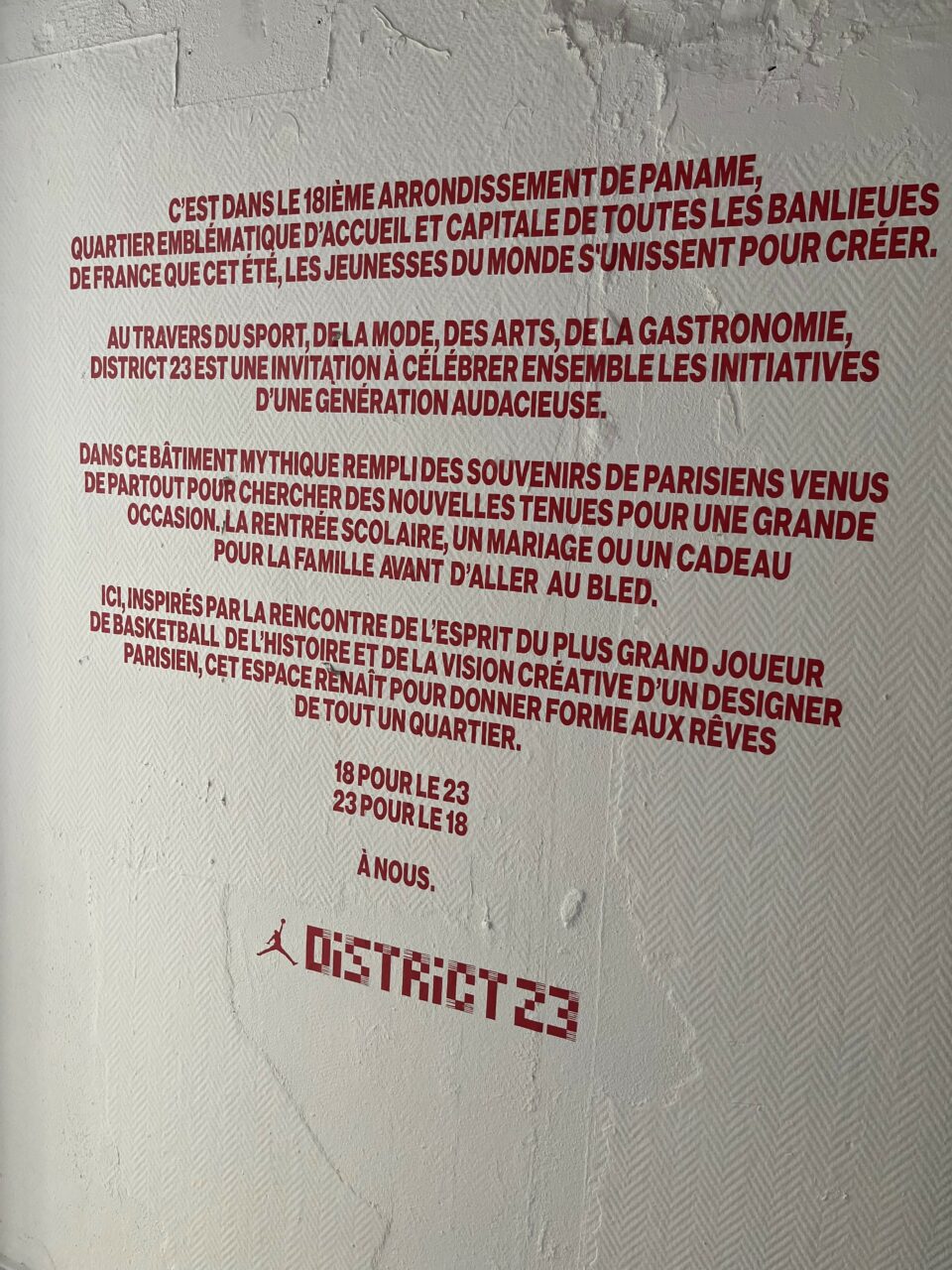

“This mythic building is filled with the memories of Parisiens coming from everywhere to look for new outfits for big occasions — going back to school, a marriage or a gift for family members before returning to their homeland,” read a text at the entrance of the installation.

Drawing on the Past to Propel Young Creatives and Athletes

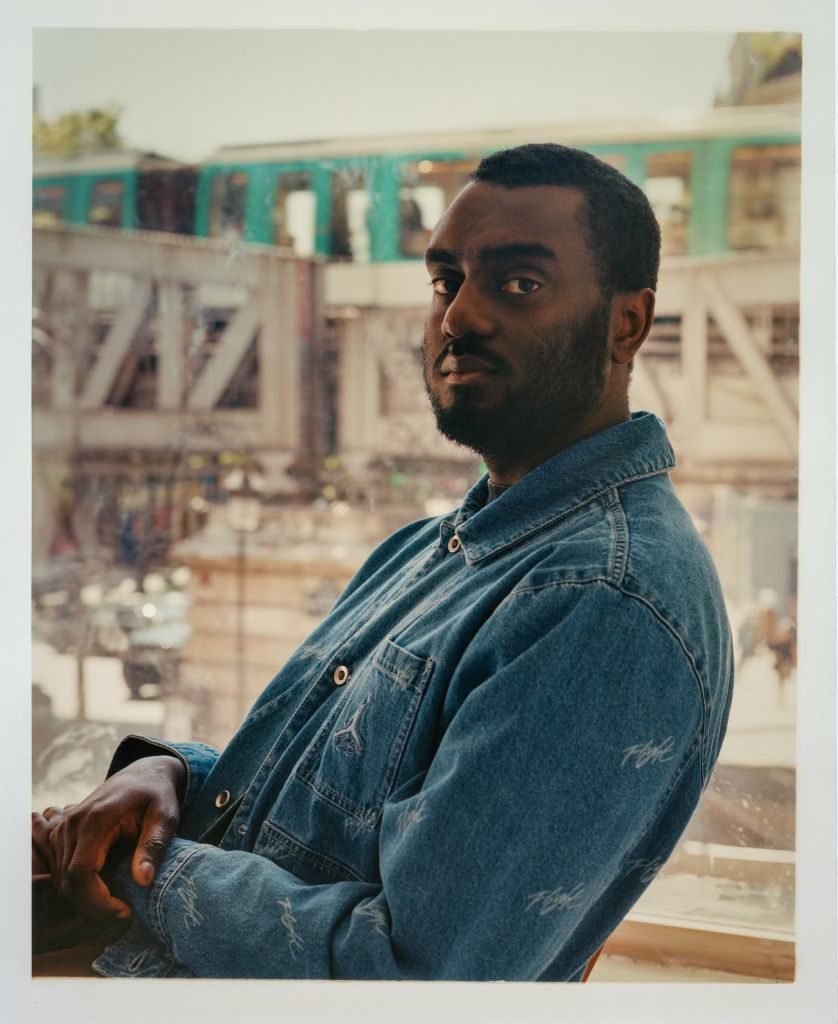

Despite a decade-long decline that led to the eventual closing of all Tati stores by 2020, including the Barbès flagship, those memories are still strong in the minds of many Parisians. Not least of these is Parisian fashion designer Youssouf Fofana, the child of Senegalese immigrants and frequent Jordan Brand collaborator. Following the store’s closure, Fofana transformed the space into the headquarters for his design-development collective United Youth International, which provides technical skills, mentorship and community for Parisian youth aspiring to careers in creative industries.

“I remember that as a child I used to step out of the Barbès-Rochechouart Metro station at the start of every new school year to go on a ritual, a search for new clothes and shoes,” recounted Fofana in the introduction of a special magazine created for the District 23 collaboration. “I’d use the big blue Tati sign, visible from the elevated metro, to find my way. The 18th arrondissement’s welcoming spirit left an imprint on me and formed my worldview: my weekends shopping alongside other families of the global diaspora at Tati; the mixing of cultures that color the tapestry of this neighborhood; the traditional West African textiles reinterpreted through the lens of savoir faire.”

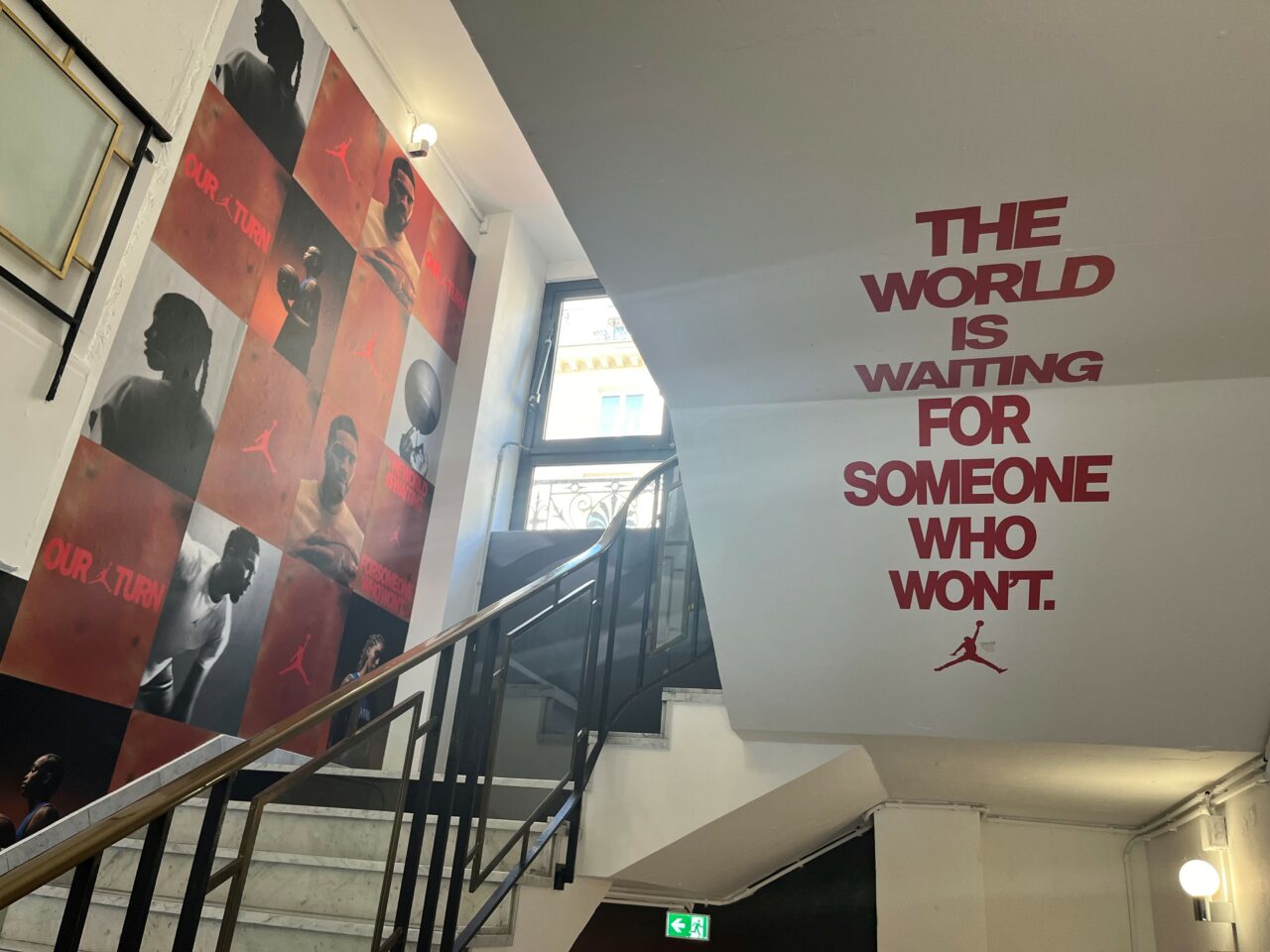

Clearly, those reminiscences also colored Fofana’s transformation of the space for the Jordan installation. While the outside of the defunct department store is still (perhaps purposefully) covered in the relics of its demise — graffiti, renovations started but not completed and old signage — inside, the space has been completely refreshed with a bright, colorful design that seamlessly melded basketball and street culture with African artistic influences.

The first floor featured a small boutique for Fofana’s fashion brand, Maison Château Rouge; a library with a collection of books on sport and culture for passersby to peruse; a live DJ; and a personalization station where visitors could choose their own screenprint designs for T-shirts, all anchored by that Parisian mainstay, a café.

The second floor was dedicated to the Diaspora Renaissance art exhibition, while the third floor, not open to the public, featured a workspace reserved for the Jordan Brand and Fofana’s “summer school” for young creatives.

Exploring Diasporic Cultures Through Food and Art

The District 23 café, which offered ample indoor and outdoor seating, paid homage to the gastronomy of the neighborhood by highlighting recipes, restaurants and food collectives that elevate cultural traditions. Among those collectives was Mam’ayoka, also known as the “mothers of the 18th arrondissement,” who served up crowd favorites such as Thieboudienne, a West African fish, rice and vegetable dish. Throughout the installation’s six-week run other emerging diasporic chefs shared their own recipes that explored traditional food through a contemporary Parisian lens.

The art exhibition on the second floor included work from 23 contemporary artists, including Gabriel Moses, Alvin Armstrong and Maty Biayenda. Curated by Fofana and Jordan Brand “family member” Easy Otabor, owner of Chicago’s Anthony Gallery, the exhibit aimed to help visitors “experience the global, interconnected nature of diasporic communities from across Africa, Asia and Latin America.” Six artists also were commissioned to produce their interpretation of the Air Jordan 1 (AJ1) through a diasporic lens to bring to life what the iconic shoe means to the culture.

‘Bringing the Story Full Circle’

The third floor featured a small display of Fofana’s own AJ1 and other collaborations with the Jordan Brand. “The coolest kids in my neighborhood were the ones who wore Jordan Brand, and Michael Jordan was who we all aspired to be, so it was a dream come true to be able to work with them on the AJ1, then again on the AJ2 and apparel collection inspired by my program United Youth International,” said Fofana in a statement. “District 23 feels like our biggest collaboration yet that brings the story we’ve been telling full circle.”

Fittingly, the rest of the third floor featured an expansive workspace where Fofana has created an immersive curriculum in the textile arts for dozens of young Parisian creatives to help them develop their design and technical skills. The programming also included training in the intricacies of starting a brand.

“This entire project is dedicated to the youth of this neighborhood and neighborhoods like it around the world,” added Fofana. “My hope was that by amplifying the 18th arrondissement to the world, we could elevate the community members’ collective pursuit to change the narrative and empower them to create a new legacy not just for themselves but for the future generations coming behind them.”