Resale is one of the hottest sectors of retail right now, but despite rampant consumer demand and brand uptake, resale platform operators are struggling to make ends meet. This dilemma was on display as two of the biggest managed resale marketplaces, ThredUp and The RealReal, reported Q1 2023 earnings on May 9.

Both platforms have zeroed in on profitability as their primary focus in the coming year, with ThredUp confirming its expectation that it will reach adjusted EBITDA break-even by the end of 2023, and The RealReal reiterating its own prediction that it will reach profitability by 2024 .

Both companies’ Q1 results do indeed indicate movement in the right direction. ThredUp saw revenue increase 4% YoY to $75.9 million and decreased its adjusted EBITDA losses to $6.6 million, or 8.7% of revenue. Total revenue at The RealReal fell 3% YoY to $142 million, but much of that came from direct sales, which declined 49%, while revenue from consignment was up 22%, reinforcing the company’s renewed focus on this side of its business.

However, this positive momentum has not been enough to satisfy Wall Street (a common challenge for companies in the retail and tech sectors). Both The RealReal and ThredUp have seen share prices dip precipitously since their IPOs in 2019 and 2021, respectively. While both companies debuted at over $20, shares of ThredUp were trading at $2.99 and The RealReal were trading at $1.32 as of May 9, 2023.

Advertisement

In the first part of this series, we examined the challenges that make profitability so elusive for resale operators. Today we’re taking a look at the different ways three resale operators — ThredUp, Thriftbooks and GoodwillFinds — are tackling those challenges and moving their businesses into the black.

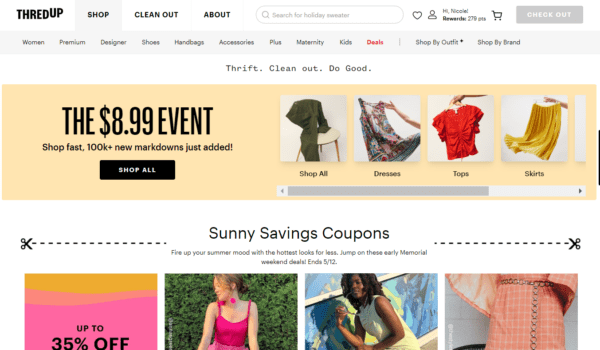

1. Charge for Your Services (like ThredUp)

Despite operating one of the largest resale marketplaces in the U.S., ThredUp now views itself as more technology company than retailer. In 2019, the company packaged the tech and logistics infrastructure it had developed to run its own marketplace and began to offer it to other brands and retailers as a white-label service. Today, the company’s Resale-as-a-Service (RaaS) offering boasts more than 50 client brands, representing a “recurring, high-margin revenue stream,” as CEO James Reinhart described it on the company’s 2021 earnings call.

Amazon has been the model for this type of monetization, from its AWS cloud services to its Fulfillment by Amazon offerings for marketplace sellers. But Amazon’s success in these areas came after years of heavy investment, and the same has been true for resale companies. ThredUp spent $128 million on operations, product and tech in 2021 and nearly $156 million more in 2022. The tide is turning though: ThredUp anticipates a significant reduction in its CapEx spending in 2023 — by approximately 60% compared to last year — thanks to the completion of projects like a new 600,000-square-foot processing facility in Dallas.

“Ultimately it’s just about getting bigger to serve more customers — as we do that, the profits will come,” Reinhart told Retail TouchPoints in a 2022 interview. “If you think about any company that’s been an innovator in the economy, whether it was Amazon or Tesla or Netflix, people always pooh-pooh the growth strategies and say, ‘These companies are never going to make money.’ We know that’s not true, because once you cross that threshold of paying back your fixed costs, you can generate enormous amounts of profit. We take the same approach.”

The company also is taking steps to improve the margins on the marketplace side of its operations as well. Earlier this year, ThredUp began testing a series of changes that Reinhart described as “a meaty experiment” in optimizing the unit economics of its marketplace. These include new fees for ThredUp’s cleanout service, which was previously free, and an increase in the “restocking fee” for returnable items from $1.99 to $3.99.

Aside from bringing in additional revenue, Reinhart noted on the 2022 earnings call in February that the modified fee structures also were helping to incentivize more lucrative behaviors. For example, sellers are sending in fewer Cleanout bags, filling those bags with more items and including higher-quality pieces, all of which Reinhart attributed to the shift in mindset “when people are paying for a service.”

The Bottom Line: The unit economics of selling secondhand goods online are tricky to get right, especially when you’re operating at the value end of the spectrum as ThredUp does (as opposed to luxury resale). By expanding its business into services as well as pulling various levers to balance out the profitability equation on its marketplace, ThredUp may be one of the first managed resale sites to make value resale profitable at scale.

[Update 11/22/23: In Q3 2023 (reported on Nov. 6, 2023) ThredUp reached U.S. quarterly adjusted EBITDA breakeven for the first time in company history.]

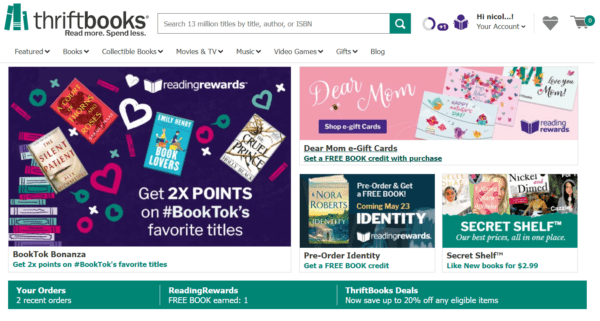

2. Get Really Good at One Thing (like Thriftbooks)

Online bookseller ThriftBooks launched in 2003 as an Amazon seller but has since become one of the largest independent sellers of used books in the country through its own site and app. The decision to break away from Amazon actually meant that Thriftbooks had to raise the price of its books, which in a category this competitive could have been a risky move.

“The business, when we broke away from it, was completely commoditized by the Amazon marketplace, which at that time was selling under a system they called ‘penny books’ — the way that you got the first listing on Amazon was you sold your book for a penny and then you charged $3.99 shipping,” explained Ken Goldstein, Chairman and CEO of ThriftBooks in an interview with Retail TouchPoints. “We decided to reclaim [the space] and sell our books at a fair price.”

In order not to compete on price, Thriftbooks leaned in on “quality, service, selection and loyalty,” in addition to low (albeit not the lowest) prices. “By focusing on [these other elements], we are building a branded relationship with our customers, so much so that our customers become our advocates,” said Goldstein.

Notably, Thriftbooks has always been able to do this profitably, according to Goldstein, who said the company has never lost money in its 20-year history. Goldstein attributes this to the company’s focus on “financial discipline” (which interestingly is something both ThredUp and The RealReal executives also pointed to in their latest earnings presentations). However, Thriftbooks also is aided by the fact that it has remained singularly focused on refining the processes for selling one specific, relatively easy-to-handle category.

Supply comes cheap for the company, which sources salvage items from charities like Goodwill and Salvation Army as well as municipal and school libraries. “We buy by the pound, and sell by the unit,” said Goldstein. The larger expense for Thriftbooks comes in the processing, grading and listing of its books, for which the company has spent 20 years developing sophisticated sorting and pricing algorithms and fully automated processing facilities.

“We understand what the sell-through metrics have to be, meaning, of the books we buy, no matter what price we buy them at, how many we have to sell and at what price to make this a success,” said Goldstein. “It all goes back to the data analytics — you can’t understand how to be profitable at this scale if you don’t have the data obsession to understand what every single transaction looks like, and what the customer lifecycle is, to understand how much to reinvest.”

The Bottom Line: Staying focused on one category and refining the systems and processes to do that efficiently have allowed Thriftbooks to build its brand and remain profitable at the same time. Other resale platforms are beginning to recognize the benefit of more niche offerings; for example, The RealReal is refocusing on luxury fashion consignment and pulling back on its expansions into direct sale in categories like beauty and home goods.

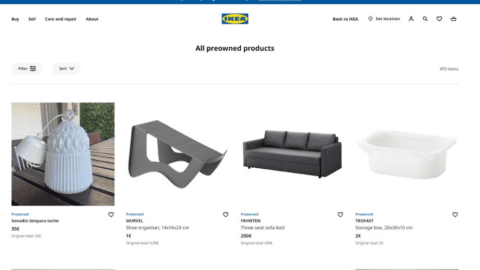

3. Leverage Your Existing Assets (like GoodwillFinds)

While both ThredUp and Thriftbooks have spent years and invested millions in building out the infrastructure to process and warehouse their inventory, the newly launched GoodwillFinds.com has a prebuilt advantage in that regard — the more than 3,000 Goodwill stores across the country.

“The managed marketplaces are consumer-focused, [while] the peer-to-peer marketplaces [like Ebay and Poshmark] are more about locking in the supply,” said Matthew Kaness, CEO of GoodwillFinds.com in an interview with Retail TouchPoints. “We’re trying to pioneer a third model by partnering with the existing physical infrastructure of our donation centers, and using technology to aggregate all that supply into a unified catalog. What we’re hoping is that over time, because of our mission and the tax-advantaged status we can give donators, we’re going to become an attractive third model for people in the space.”

While GoodwillFinds doesn’t have to invest in the capital-intensive process of building physical infrastructure, it does need to build out the technology. To that end Kaness is rapidly staffing up with “technologists, designers, product managers, analysts and data architects,” which he believes will be “a huge catalyst for our success.” Among the new hires are two industry heavyweights — former Walmart and The RealReal exec Nicolas Genest just joined as Chief Technology Officer, and new Chief Revenue Officer Jim Davis who hails from leading retailers including Office Depot and Urban Outfitters.

Because it operates as a nonprofit (like its parent company), GoodwillFinds is under less pressure to turn a profit than its competitors. Nonetheless, if the platform can’t become self-sufficient financially, the effort will likely fail.

Kaness is counting on the Goodwill brand’s high name recognition among American consumers to help keep acquisition costs down. GoodwillFinds also benefits from the fact that “the impact [of a purchase] is what people care about in this day and age,” he said.

“People have a lot of options to shop secondhand online today, but I think the knowledge that the proceeds of your purchase [on GoodwillFinds] go back into the community where it was donated to fund social impact causes — and that this is a new venture from an organization that has been one of the pioneers of sustainability — will make it easy for shoppers to choose to support us versus another platform,” Kaness noted.

The Bottom Line: GoodwillFinds has enviable advantages in the form of essentially free supply and a ready-built processing infrastructure in the form of donation center locations and staff. The success of the enterprise will hinge almost wholly on the technology they build to create an effective online shopping experience that meets the high expectations of today’s digital shoppers. No easy task, especially when you consider that unlike most of its counterparts GoodwillFinds is not focused solely on a few key categories, but rather aims to sell products of all kinds — just like in its physical stores.